Ding Xiaojie (D): Where are you from? Where do you think is your native country?

Lei Chak Man (L): I was born in Hong Kong in 1977, and my family moved to Macau when I was eight years old. Subsequently we moved to Canada in 1989. And in 2008 I relocated to Beijing.. If ‘native country’ represents the idea of ‘home’, then I think it is Beijing.

D: Can you talk about your education? What are the artists that you liked the most when you were in school?

L: I studied under the tutelage of Vancouver-based artist Frank Tam when I was sixteen, and I went to the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto. I received my MFA at the university of Western Ontario.

I can easily say that I like certain works by certain artists, or perhaps some aspects of their ways of thinking, or may be the kinds of ‘gestures’ that they respond to under their specific social and environmental contexts, and not what an artist represents as a whole, including their complete oeuvre and personalities, etc. An artist is not a self-contained entity. They are influenced, nurtured, affected, infiltrated, and interweaved through and by external forces. Looking attentively at the oeuvre of an artist, one can discover that works in some periods can be very touching, but in other periods they are not as effective. Now, I still enjoy the Onement series that Barnett Newman has produced after the age of 43. For me, this series of work represents resilience and persistence.

D: When did you move to China? And why did you choose to stay in Beijing?

L: I came to Beijing in 2008. At the time I finished my thesis that focuses on the subject of ink, and I thought I needed to find out more about its production process. The most obvious place to go to for a deeper understanding of the ink culture was China. But fate took its several turns, and it wasn’t until 2013 that I had the opportunity to visit the ink-making factories in the Anhui province with the invitation of Professor Liu Jichao.

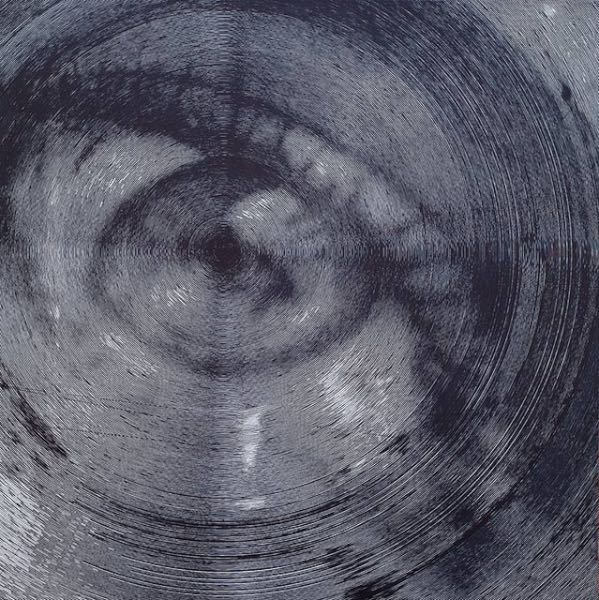

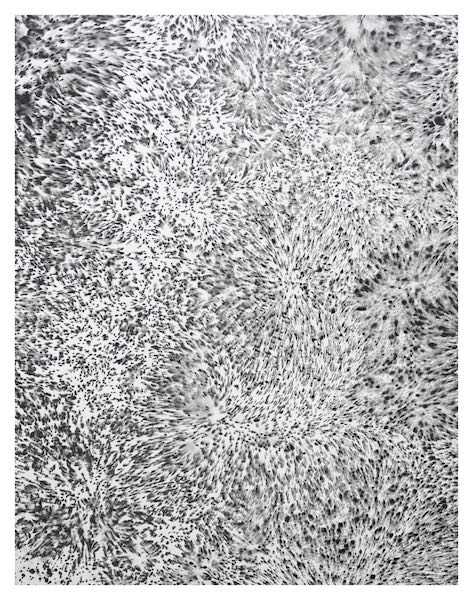

#1171, 120 cm x 120 cm, felt-tip marker on paper, 2013

D: What are the differences between living in Beijing and in Canada?

L: Living and maintaining a studio practice in Beijing, one can often sense a state of extreme polarity. The kind of unfamiliarity between people, the conflict and the inequity are all too extreme here; the contempt, the inhumane are all very noticeable. Why can’t we be peacefully together? There is this imminent explosive quality in the air, a kind of unmanageable, constantly changing flux. This is what I didn’t experience when I was living in Canada. But it is also only in China did I for the first time witnessed a sense of deep fragility, of care and of cultivation, and the bonded sense of tradition that transpires from the bone of the locals so to speak.

D: How do you survive as a full-time professional? Do you see yourself as a drifter in Beijing? And what do you think about the idea of staying adrift in Beijing?

L: Perhaps it could be more meaning to look at this question from a different angle: Living as an artist, what is considered ideal? A while ago I received replies from a few friends, and most of their answers are: being able to survive is all that’s needed. And it is true; being able to survive means one can continue one’s practice. I am the type of person who will seek out money when all the food is emptied out from the fridge; while the rest of the time I stay in my practice. When I first arrived to Beijing I needed to pay rent, and at that time I had help from Zhu Qi. I did editing work for the Art Map for a full year. After that I did a year in a gallery and have done translation and proofreading work to survive. This is how I carried on and continued my art practice.

Staying adrift is like drinking water; there is nothing strange about it. Being a kind of drifter in Beijing is itself not a bad thing. In Beijing everyone drifts; everyone is in a state of the process.

D: What are the books that you normally read? What is the connection between your work and the books that you read?

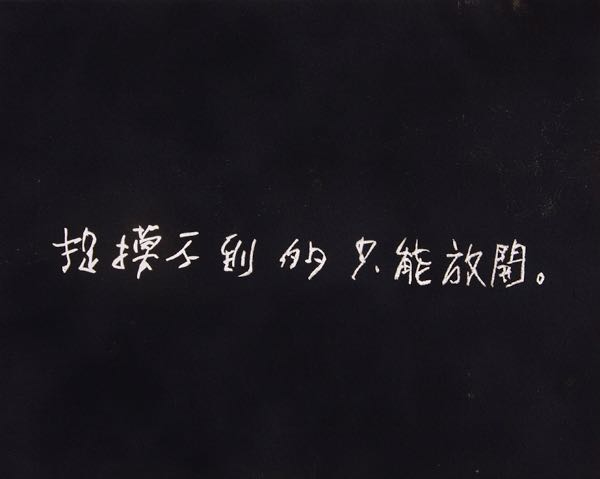

L: I am interested in flipping through sci-fi and comic books to books on archeology; the books that I read most often do not have a direct connection to my work. Except for the purpose of doing research, I don’t tend to read with an intention in mind, and I oppose to directly taking content from a book as an ‘explanation’ for a work of art. Words are words, a line is a line, they can form association by being together, but the feelings that they communicate are different. Words can be used to describe a state of mind, to describe a work of art, but we need to be careful to distinguish the words from the work of art itself. A work is a work; by learning about it, it is supposed to touch us even more intuitively. We have to be sensitized in order to experience a work—there is no need to speak. Reading a book is an enjoyment; it is a means to open up our eyes. Reading books, watching videos, listening to music and podcasts, attending exhibitions, living life—this is the process of assembling and accumulating, it is about listening to the numerous and the diverse. We are all in the process and we are all walking the path in life.

D: Which book are you reading right now? What are some of the points that inspire you?

L: The past few days I have been reading a dictionary borrowed from a friend. It is called The Deleuze Dictionary. I can’t say that the ideas and information I received have inspired me; for me, inspiration is a word that carries the weight of greatness and immensity. I was merely reading up on Deleuze’s persistence on ‘intensity’…

D: What are some of your hobbies? Are you someone who likes to have fun in general?

L: To play is very much like art making, it is a kind of expenditure. What is expended are manpower and material resources. I love to play, because playing itself is happy, and art making isn’t. The activity of art making is tasteless and timeless; it is about experiencing a sense of the present without a past. Art is about the heart rate and the blood flow. To play, to enjoy oneself is about the heart rate and the blood flow, plus joy. It is important that we make that clear.

D: Can you talk about the changes in your work over the past few years? What are the sources that encouraged these changes?

L: Perhaps it is not noticeable just by looking at the works, but in the past few years, I have noticed a large part of my creative process is to experience failure, to comprehend the humility of the material, and to explore the restrictions that I have given myself. The creative process is not one about delight, joyfulness, or experiencing freedom—it slowly becomes apparent that by being in the creative process, one can see ones limits, one’s weaknesses and constraints. For me, this is a painful realization. But don’t be misunderstood; the creative process is not a struggle, because you can always choose to stop and go for a coffee, to meet friend or to watch a movie; you can, at any time, choose to cover up your weaknesses, to choose to forget about reality and not to think about meaning. I believe that the work produced can and will ultimately reflect an understanding about the self and the precariousness of existence itself. Similar to keeping a plant alive, the growth of a creative practice requires the fertilization of time. That’s why I believe that an art practice is a daily, uninterrupted one. Bearing in mind constantly, that’s all that’s needed. The result will gradually become apparent.

D: What sorts of medium do you use for the works? And why do you choose to use these mediums?

L: In the past ten years, the material ink has always taken an important role in my practice. The ink-making process in the past required the burning of pinewood in order to extract its ‘essence’—pine soot. The transformation from a pine tree to becoming an ink stick requires a series of labor-intensive, unnatural processes including burning, steaming, hammering in order to produce a dark black ink stick with a purplish sheen. From the Neolithic period all the way down to the present, ink has not always been used only as a decorative material, a material for writing, keeping taps on information, art making, or even as medication—these are cultural artifacts. Ink does not only represent the history and tradition of the past thousands of years, it also, most importantly, encompasses the past, and it points to our destining—transformation and death.

D: How do you interpret ‘tradition’? In converting tradition from the non-Chinese to the Chinese, do you see yourself as been more advantageous because of the cultural association that you possess?

L: From the moment when the Internet was popularized, cultural association is no longer one of advantage or disadvantage. What we possess now is difference. Under the shadow of globalization, what we still possess is our laziness towards knowledge and realization, our ignorance, our discrimination and hatred towards others, and the hidden violence that is ubiquitously found. Someone once said to me, history is disgusting. But we cannot avoid not being in the stream of history. And it is really history that manifests our traditions. Tradition, very much like history, is made of blood. Without blood, we will not have tradition, and we certainly will not have ourselves. Tradition is not something that pushes us to struggle forward; tradition is what permeates through our use of the body.

D: How do you comprehend the idea of ‘nature’? What distinguishes the ‘nature’ of the past and the ‘nature’ of the present? Is ‘nature’ present in your work?

L: Who can really believe in the existence of nature? Does nature really exist? When we see the beautiful mountains and streams and the hand-drawn calligraphy inked by the ancients, why do we think that these are the manifestations of nature? Who tells us these are the representation of the combine effort of nature and of human? We tell ourselves that we must head towards nature, but do we know what nature is? I don’t. The Internet, cold medication, supermarket, taobao—these are not natural, but they are the closest to us and we take advantage of them naturally. They are second instincts to us. Human beings are animals, and animals in their most primordial, natural state are savage, violent, barbaric and primeval.

D: Often art cannot be disassociated from its relationship to the concept of time, and all of art’s elucidation cannot be detached from the concept of time either. Some artworks tend to lean towards the process, while some focuses on the result. A lot of novel conceptions can also be derived out of time. How do you understand time? What arouses your interest in your conception of time?

L: What I know about time is that it repeats and that from its repetition, differences emerge. From the everyday routine, the eight hours sleep, the two meals, the recycling of previous artworks in the making of a new piece, and the repetitiveness of the creative practice—these are all signs of recurrences and repetition. But repetition itself does not truly signify the movement of time. Let’s consider this: the clock is ticking repetitively, but its battery power is slowly being drained away. The human body, going through the recurring cycles of the seasons, and in time, becomes weak and old. The body fattens when one eats too much; this is the difference that our body experiences over time.

The creative practice is one of repetition. Before starting a new work there existed a prolonged duration of thinking and consideration. Sometimes when a work has come to an end, it may take another several more years before further work will be done over the piece, or that it may multiply and become a series of works. The deposition of time enables us to go back and tease out more potential meaning from something that we have done in the past—and this tells me that time is non-linear. The continuous repetition produces discrepancy as it slowly spirals towards entropy. Sometimes we return to a distant past, and sometimes our steps will take us to unfamiliar territories. Time is made up of instances, and in the process of a creative practice, one may experience time as compressed and at another instance as extended; time is soft and pliable. This is what I know about time.

D: In your recent works, one can see that you are moving away from the ‘image’, away from the everyday and the body that are found in your earlier work. Your new pieces are almost—image-wise—unrecognizable. Is this the most apparent change in your work in recent years?

L: The most apparent shift in the past few years is discovering my practice has evolved from being in a state of scattering to becoming more congealed, and that the process of filtering from the variously diverse is more refined. I am becoming more attracted to distant things that possess a temporal dimension and a spatial span. This is similar to that of a spiral. A vortex.

When I was younger, my family was in the business of selling archaic jade. The touch of jadeware is that of ice-cold. The minute grooves were ‘carved’ from a time of remote antiquity, and I imagined that lava had probably spurted out from the Earth’s crust and resulted into the rock that I held in my palm. Unknowingly, I sensed that I have bridged the distance between the igneous matter—its physical attributes—and myself. It took me a very long time to comprehend the transformative quality of matter is not dissimilar to our hundreds of thousands of years of evolution, the thousands of years of our cultural mutations, the hundreds of years of our changing ways and attitudes of thinking, and the decades that it takes for our body to slower disintegrate. The accumulation, stratification, weathering, fissure, crystallization, density of a pebble seem to be a metaphor of our biological morphogenesis, of the substance of our own state of formation and transformation. We may be standing on a hard, solid boulder, but time has always been hovering over our heads, compelling us to change and to grow old in this transient and fragile life, just like the solid ground that we stand upon. The shifting of the tectonic plates, the compacting and cementing of clay, sand, pebbles, cobbles and boulders, the massive proliferation of CO2, the extinction of endangered animals to the depletion of hydrogen fuel in the sun—everything is changing. Everything IS change. These observations filter through our bodies and connect with our intuitions, and through a period of consideration, the interpreter seeks an interpretive method through the means of making a thing.

D: Do you think of your work as abstract or are they ink and water-based?

L: I don’t know. But I know that my practice is more accustomed to seeking the multifarious and the unfixing of my ways of expression. I am on a mission to making a portrayal of the world. We return to way too much repetition in our lives everyday, and the idea of change becomes a luxury that is very far removed from us. Seemingly. But really this is not true. We are just afraid of change even though we are undergoing it every second. I am often very afraid of change.

D: Generally speaking, what motivates you to start a new series of work? Is ‘process’ an important factor to consider in your practice?

L: Suppose if we try to imagine that, right now, the way we behalf, the way we think, act, the way we treat others is not motivated by a sudden conception of an alien power, but through years of cultivation, absorption, digestion and assimilation, and through the repeated experience of failure and more than once, rejections; what we visualize from the sight of words, what we hear from the overwhelming noise of the crowd, the experience gathered from the felt sound of the ocean waves, then we can perhaps imagine that the motivation for different creative urges, or the production of the series of works, has the potential to always have been there, that such potential is continuing to being amassed, waiting to be surfaced.

We receive a lot of interference in our everyday lives. But sometimes we may encounter a phenomenon that triggers a forgotten memory, and this piece of memory happens to be stitched to other sporadic thoughts. And over time, we pick up sounds of its recurrence here and there; it gets repeated in our mind—there is playback. And all of a sudden, this thought, which is now mutated, is prioritized in our consciousness and we may be urged to bring it into manifestation. But how does one manifest an intangible sensation? This sensation is proteus, it can easily slip away from our fingers. Perhaps one may choose to use matter to convey this internalized but externally motivated sensation. One also begins by searching for the proper medium, conducts a series of experiments and trials, and from the results gathered one decides what to take and what not to take. Further tests will be done to bring the result closer to what one had sensed. The work grows from a serialized, morphogenetic, repetitive and unstable process. The core of the work is always process.

D: How do you think an artist balances between emotional and rational thinking?

L: Why does an artist need to balance between the emotional and the rational? Balance means to exercise restraint and control for one side, and to allow indulgence and limited prohibition for the other. Artist lives each day doing what they want to do is already enough.

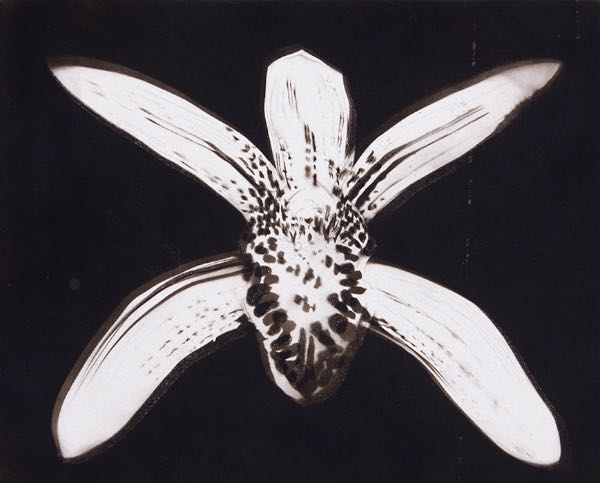

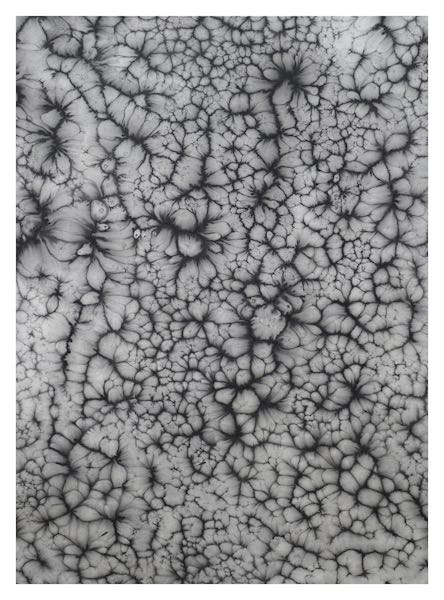

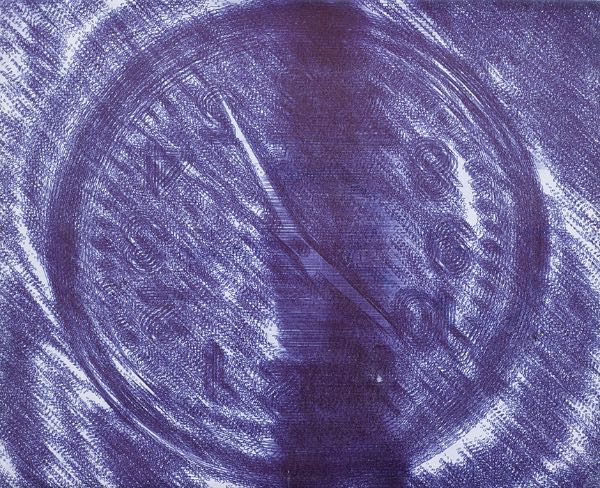

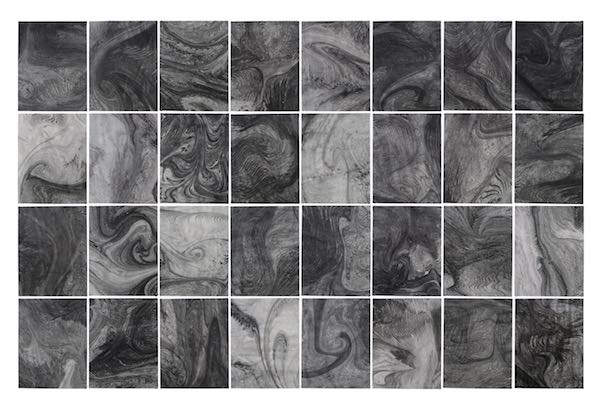

#1166, 30 cm x 24 cm, Ballpoint pen on paper, 2013

#1161, 30 cm x 24 cm, Ballpoint pen on paper, 2013

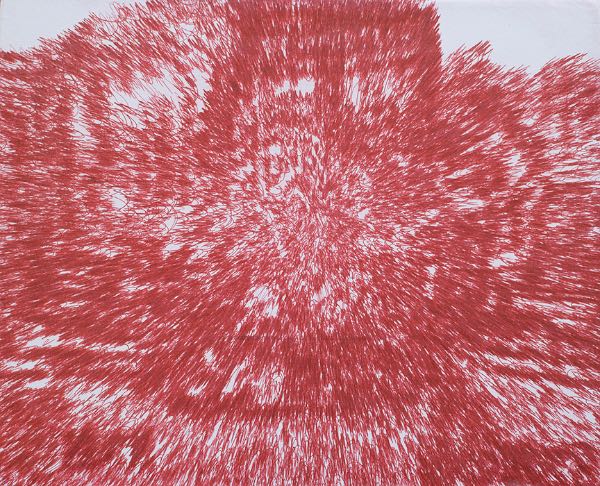

#1172, 244 x 157 cm, Ballpoint pen on paper, 2013

D: You have used the color blue and red in your ballpoint pen series. Why did you choose these two colors? I notice now that you have abandoned colors, and you only use black, white and gray to compartmentalized the spatial in your work.

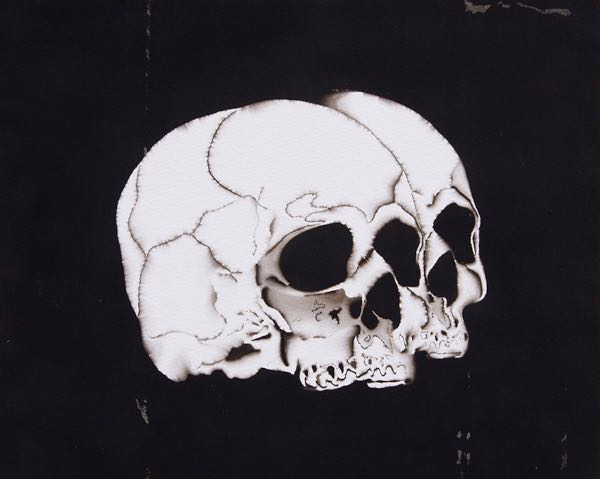

L: In 2013 I did a series of ballpoint pen drawings. These works are an extension, a branch, and a category of my ink-based practice. Ballpoint pen is becoming an obsolete medium; it is in the process of being abandoned and is a tired and passé instrument. Its color signifies a period in time, a memory in time. This series of works are sorrowful and disheartening. The depictions were traffic accidents, deceased victims, the passage of time, and the nostalgia to tradition. The subject matter orbits around the idea of an inattentive existence, of the coming and going of time, and the moments of death that often just brush us by.

These works and their subject matters have influenced my practice, and its shadow can be found to my current work. Some of these subject matters—for me—are more sensitive, so I decided to choose a more indirect, a less human-interfering method to make these works. I used a computer drawing tablet, a software and a plotter as tools to mediate around these sensitive subject matters. I have always been very sensitive to the use of color; it has always been a problem or may be even a suspicion to choose specific colors to make a work. The red and the blue colors of the ballpoint pens are filled with meaning; color resurrects certain cultural associations.

#1055, 56 x 76 cm, Ash on paper, 2007

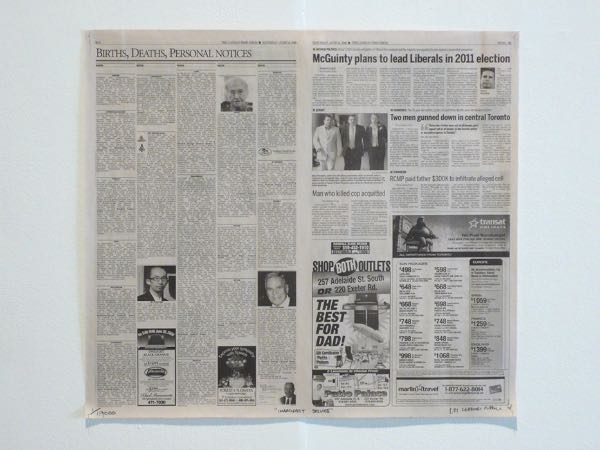

#1069, Published in The London Free Press on June 4th, 2008

D: How much does ‘destructiveness’ play a role in art nowadays? Does it exist in your practice?

L: Similar to the hypothesized evolution of a large star that turns a supernova, and through an imminent explosion that produces a blackhole, this process is a destructive one, but it seems also more like a transformation, a conversion. In 2007 and in 2008, I executed two works that are about destruction/conversion. #1055 (2007) is a self-portrait made from the grinded up ashes of burnt artworks that I have made previously. #1069 (2008) is an obituary listed in the newspaper The London Free Press. Through the act of burning and collecting the leftover remains, the former work stresses on the idea of converting the ‘dead’ material into an energized entity so that it can form a dialogue with the viewer. It is a work of art, and it speaks—conceptually—of the condition of death. This is a very optimistic work, and it is full of hope that touches on the evolution of substances, matter, and of the self. The latter artwork is an extension of the former, and it actively injects this hope to the everyday reality by participating in reality itself. Two thousand copies of The London Free Press were distributed in the public sphere, and it brought with it the true meaning of death to the people in the community. Nowadays, I still occasionally burn my works; works that I considered unnecessary. I want to minimize the space that it occupies, because its existential meaning does not deserve to occupy that much space.

编辑:丁晓洁