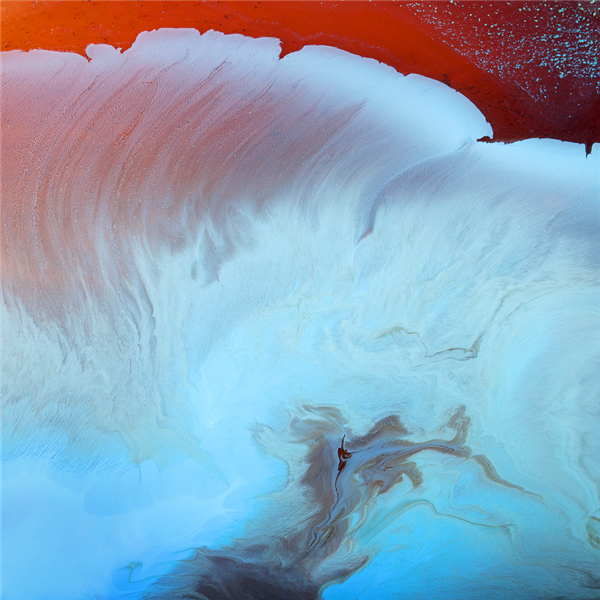

洄01 60X60CM 数码绘画 2016

认识少英多年,当真要写点什么,却难而入手,因不少学者已为她写过评论文章,珠玉在前;作为邻居和同行,尝试描写我眼中吴少英其人和她的创作。

吴少英早年在澳门受艺术启蒙后,前往伦敦大英博物馆的中国书画藏品馆硏究室钻研古今重要中国藏画,锻炼了她的眼力;旅居台北十年后驻京创作至今,她兼具澳港台欧身份,可谓世界公民,国际化的经历和视野,使她不拘泥于单一或传统的艺术手段;然而,中国人的水墨精神还是植根在其基因之中,“洄”系列作品便是少英“不择手段”追求中国艺术核心“意韵”的最新成果。

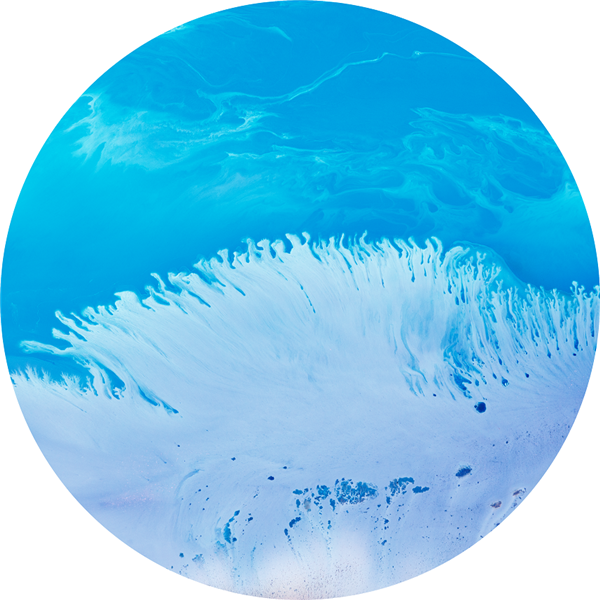

洄11 70X70CM 数码绘画 2016

在先秦民谣中“洄”(驻1)曰水之回旋,兼有尽善尽美之意,暗合少英对艺术创作的完美追求。

古时一位国家档案室管理员悟“道法自然”(驻2)后,历代画家便以“外师造化,中得心源” (驻3)为艺术终极追求,少英的创作以人文为本感悟天地。苦瓜和尚于明清之际高呼“一画之法……无法生有法” (驻4),数百年后才有吴冠中的“笔墨等于零”声援;互联网时代的今天,“笔墨当随科技”,少英的数码创作虽是新载体,或许百年以后已是彼时的传统。

洄11 70X70CM 数码绘画 2016

少英艺术风格的来源,有感于人类文明发展至使水土破坏和自然资源枯竭;信手拈来被舍弃的酱油牛奶与其他生活弃置物,即是她的水墨和颜料,既是艺术家不浪费任何资源的天性使然,也是她对周遭生活环境日益污染的悄然反抗。

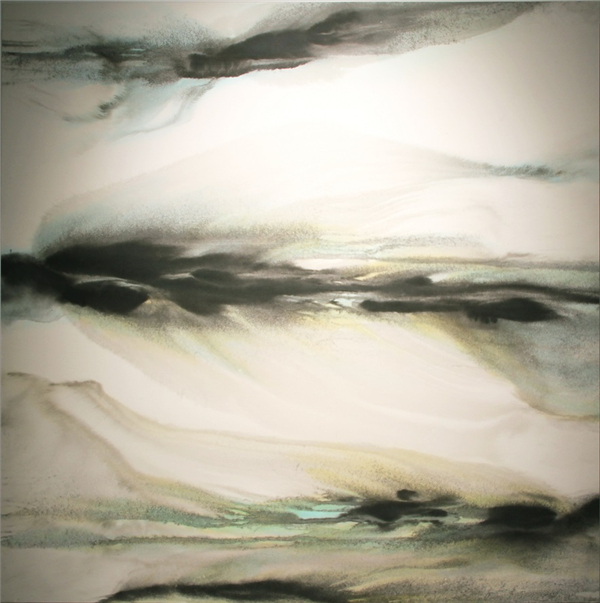

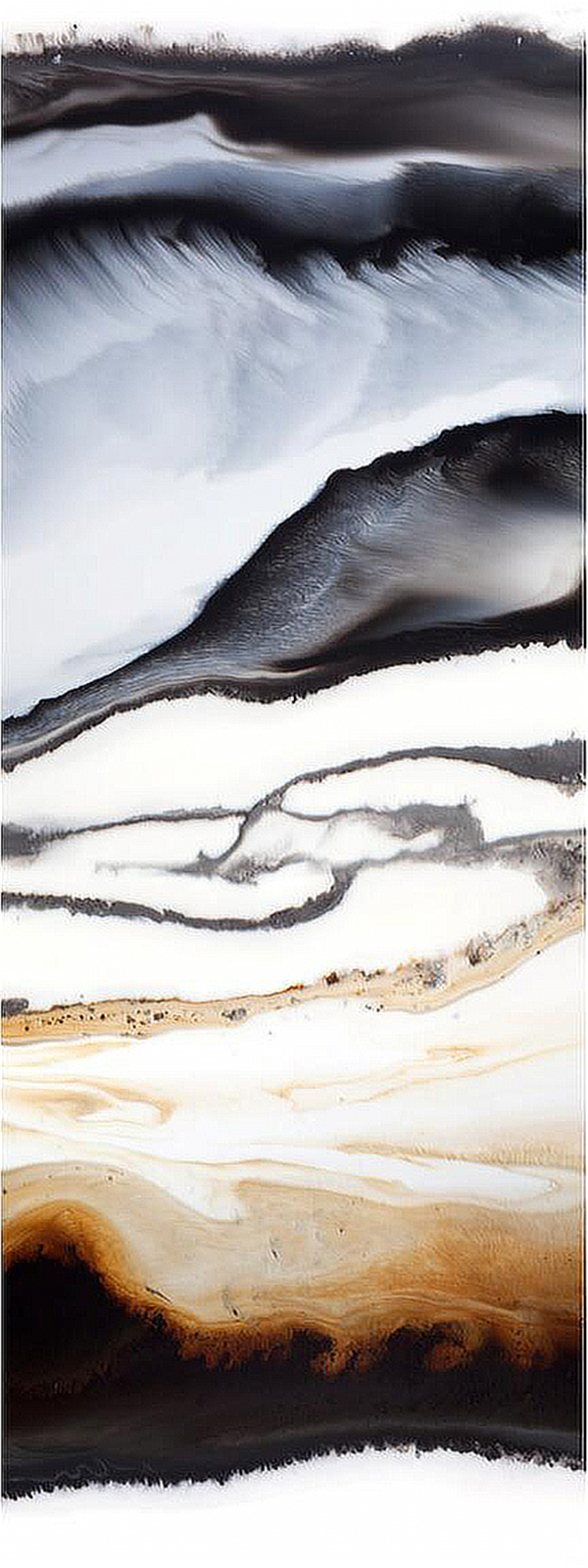

少英的早期作品,以宣纸和画布为载体,纤维宣纸层层吸墨的特性,墨色的层次向下生根,灰而淡雅;画布表面胶质的底材让墨色向上层叠凝聚,黑而乌亮;表面看同是平面,内涵却是一阴一阳的两个系统。近年,环境保护和柔合阴阳是少英自身艺术探索的重要课题,各种数码新技术的尝试也是以此为前提的试验;古人留白,少英则以牛奶“冲白”,酱油“守黑”,当各创作元素冲进玻璃板的瞬间,数码相机和摄像机成为她的画笔和宣纸,快门绝妙地保留作品生成时那唯一的完美的“一刹那”,与其说是数码映像作品,不如说是一场水墨演义的生动记录,然阴阳则融合于混沌的数码世界之中。其最新的映像作品,“声色俱厉”,气魄逼人;利用最新科技为载体,呈现她创作中“穷天地之神变,测宇宙之幽微” (驻5)的特点。

洄13 150X100CM 数码绘画 2016

多年来,鉴于吴少英美妙地柔合当代水墨和科技之长,作品极具观赏性和易于收藏;大量中外私人收藏之余,不少著名美术馆和机构(驻6)如国立台湾美术馆,香港中国银行,上海LV旗舰店等收藏及展出其作品。

最后,要感谢“不同艺见”艺术中心同仁大力支持,“洄”得以向观众呈现,希望大家在欣赏作品之余,关注身边的环境变化和保育。

伟康

2016年秋写于京港之间

墨7713 120X120CM 宣纸 墨 丙烯 2013

驻1:洄——出于《国风·秦风·蒹葭》,蒹葭苍苍,白露为霜。所谓伊人,在水一方。溯洄从之,道阻且长。…………

驻2:道法自然——出于出自老子「道德经」第二十五章「人法地,地法天,天法道,道法自然。」

驻3:传出于唐朝的画家张璪,其行迹见于《历代名画记》和《唐朝名画录》。

驻4:出于石涛“画谱”,苦瓜和尚画语录定本,一画章第一。

驻5:出于唐朝张彦远《历代名画记》,“……穷神变,测幽微……”。

驻6:吴少英作品主要机构收藏:

巴黎半岛酒店

国立台湾美术馆

台湾新北市立联合医院三重院区

台湾桃园国际机场国泰航空贵宾室

香港国际机场国泰航空贵宾室

香港中国银行

澳门艺术博物馆

北京今日美术馆

北京香格里拉嘉里酒店

上海中欧国际工商学院

上海凯宾斯基酒店

上海浦东四季酒店

上海LV旗舰店

深圳关山月美术馆

苏洲洲际酒店

湖北美术馆

散步1300 270X110CM 绘画摄影 2013

Romantic Rhythm: A Cindy Ng Solo Exhibition

I have known Cindy Ng for many years, but when it came time to write something for her, I wasn’t sure where to begin. Several scholars have already written essays on her work, so everything wonderful that can be said has already been said. As a neighbor and colleague, I will attempt to share how I see Cindy and her work.

Raised in Macau, Cindy became interested in art at an early age. She also had the opportunity to refine her eye studying important Chinese paintings in the British Museum’s Chinese Painting Study Room. After living in Taipei for about a decade, she moved to Beijing. She has ties to Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Europe, which, in my view, makes her a citizen of the world. Her international experience and perspective means that she is not restricted to a single artistic method or to a traditional range of techniques. However, the spirit of ink is rooted in every Chinese person, and the Romantic Rhythm series is the culmination of Cindy’s unrelenting efforts to pursue the moods and rhythms at the core of Chinese art.

In pre-Qin folk songs, the Chinese character hui (1) meant “the whirling of water,” but it also implied the peak of perfection, which echoes Cindy’s pursuit of excellence in her work.

After a national archivist in ancient times realized that “the law of the Dao is its being what it is” (2), the ultimate pursuit of the painters of the past was “taking the exterior from nature and the interior from the heart.” (3) Thus, Cindy’s work attempts to understand heaven and earth through humanity. As the Ming dynasty faded into the Qing, Shi Tao advocated “the one stroke method,” which was “a method born of no method,” (4) but it took several hundred years before Wu Guanzhong said that “brush and ink equal zero.” In the internet era, “brush and ink follow technology,” and in that context, Cindy’s digital work represents a new medium, but it may also be what is considered “traditional” one hundred years from now.

Cindy’s artistic style stems from her reflections on the development of human civilization, the destruction of water and soil, and the exhaustion of natural resources. The soy sauce, milk, and abandoned objects around her serve as her inks and pigments. She uses these materials because instinctively dislikes wasting any resource and because they serve as a form of tacit resistance to the gradual pollution of the environment around her.

Cindy’s early works were painted on Chinese paper and canvas; the layers of fiber in the paper absorb ink, so the ink takes root in these layers, becoming greyer and more refined. The tacky ground on the surface of the canvas allows the ink to condense into a glossy black; it looks like a plane, but it actually connotes the two systems of yin and yang. In recent years, environmental protection and the soft interplay of yin and yang have been important issues in Cindy’s artistic explorations, and her experiments with digital technologies have also been centered on these themes. Where the ancients left voids in their paintings, she creates a “rush of white” with milk and a “reserve of black” with soy sauce. In the moment that these creative elements burst in front of the glass pane, a digital camera becomes her brush and paper. The shutter ingeniously preserves the perfect moment of the work’s birth, such that it might be better to call her work a vividly-recorded epic in ink, not simply a digital video. She blends yin and yang into a chaotic digital world. Her most recent works are harsh and severe, daring and forceful. Using the latest technology as a vehicle, her work “reveals infinite changes in heaven and earth and fathoms the subtlety in the universe.” (5)

Over the years, Cindy has cleverly combined contemporary ink and technology, making her work both covetable and collectible; Chinese and foreign private collections, as well as several renowned art museums and institutions have collected and exhibited her work, including the Taiwan Museum of Art, the Bank of China Hong Kong, and the Louis Vuitton flagship store in Shanghai.

Finally, I would like to thank our colleagues at Another Art Center for their strong support. I hope that visitors will enjoy Romantic Rhythm, and I’m sure that the works will inspire increased concern for environmental change and conservation.

Gary Mok

Autumn 2016, somewhere between Beijing and Hong Kong

1. A reference for the character hui can be found in Book of Odes: Lessons from the States: Jianjia: “The reeds and rushes are deeply green, / And the white dew is turned into hoarfrost. / The man of whom I think, / Is somewhere about the water. / I go up the stream in quest of him, / But the way is difficult and long.”

2. “The law of the Dao is its being what it is” comes from a line in Chapter 25 of Laozi’s Daodejing: “Man takes his law from the Earth; the Earth takes its law from Heaven; Heaven takes its law from the Dao. The law of the Dao is its being what it is.”

3. This comes from Zhang Zao, a Tang dynasty painter, the traces of which can be seen at Notes on Famous Paintings of the Past and Famous Paintings of the Tang Dynasty.

4. Adapted from Shi Tao’s book on painting. He elaborates the “one stroke” method in the first chapter.

5. Adapted from “to reveal infinite changes and to fathom the subtle” in Zhang Yanyuan’s Notes on Famous Paintings of the Past.

编辑:隋萌